Tramp the Dirt Down

Thursday, May 18th, 2017 • Politics / Writing

Roger Ailes made his public debut in the early pages of Joe McGinniss’ landmark book The Selling of the President 1968, a brilliant first-hand study of how filmmaking and advertising techniques permanently altered the political landscape during Nixon’s landslide election that year. McGinniss argues that the postwar, television-era thinking of Marshall McLuhan and other pioneers of media study (whose work is so quaint by modern, post-MTV, post-Twitter standards that mentioning McLuhan even in a historical context has gone permanently out of fashion) did such damage to the fabric of American political discourse that recovery is (to McGinniss’ Watergate-era thinking) probably impossible. And Ailes is right in the middle of it, a television producer coming off of talk television:

Roger Ailes, the executive producer of the Mike Douglas Show, was hired to produce the one-hour programs [the famous Nixon question-and-answer series of neo-Town Halls, now made available on YouTube by the Nixon Foundation]. Ailes was 28 years old. He had started as a prop boy on the Douglas show in 1965 and was running it within three years. […] Richard Nixon had been a guest on the show in the fall of 1967. While waiting to go on, he fell into conversation with Roger Ailes.

“It’s a shame a man has to use gimmicks like this to get elected,” Nixon said.

“Television is not a gimmick,” Ailes said.

McGinniss’ eyewitness account elaborates in detail on how Nixon’s victory was achieved through the strategic replacement of dry statistics and policy positions with painstakingly crafted short film pieces and interview segments, all designed to convey Nixon’s “qualities” through the blatant application of cutting-edge advertising techniques. (Remember that Don Draper’s fictional firm worked on the unsuccessful 1960 Nixon campaign during the early seasons of Mad Men.) At the end of McGinniss’ narrative (as Nixon triumphs), old-school journalists Jimmy Breslin and Murray Kempton are “having a sad drink together,” having completed their obituaries for Democratic opponent Hubert Humphrey: “We are two nations of equal size,” Kempton wrote; “Richard Nixon’s is white, Protestant, breathes clean air and advances towards middle age. Hubert Humphrey’s nation is everything else, whatever is black, most of which breathes polluted air, pretty much what is young […] There seems no place larger than Peoria from which [Nixon] has not been beaten back; he is the President of every place in this country that does not have a bookstore…”

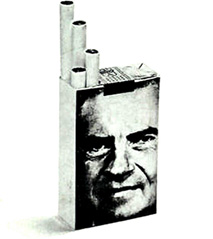

Almost fifty years later, as bookstores, too, are fading into the past, the continued legacy of that first television-based campaign Ailes masterminded is, needless to say, not just still with us but dominant and triumphant. As Leni Riefenstahl did with movie cameras and Joseph Goebbels did with radio, so Ailes did with television—a lost-wax technique whereby delicate political meanings are melted away and the remaining hollow mold of “TV news” filled with the immutable bronze of emotions and impressions. The chain of causality that leads from Nixon to Reagan (and the force of Peggy Noonan’s rhetoric) to George W. Bush to Donald Trump is assembled from links like Cokie Roberts’ assertion that Hillary Clinton’s transgressions, though imaginary, were “out there” (meaning, being discussed by the public) and therefore warranted further journalistic scrutiny; by Karl Rove’s infamous declaration that “an empire” like the United States “makes its own reality;” by Frank Bruni and others insisting that Bush won the debates with Gore by “appearing Presidential” (rather than sighing “arrogantly” as did Gore); and finally back to Ailes himself, in his curtain call as Trump’s most vital supporter throughout 2016 (and, of course, as fellow serial abuser of women).

A subtext of Citizen Kane was the replacement of the Hearst empire (newspapers)—represented by Kane—with the Luce empire (newsreels; the “picture magazine” etc.)—represented by Thompson, the reporter whom we follow through the movie. Neither of them are particularly good at getting to the truth, but both are influential in a sub-rational way (“You supply the prose poems; I’ll supply the war,” as Kane tells his reporter covering the nonexistent Cuban war, repeating Hearst’s alleged words) and the newsreel that we see provides a near-operatic context for the events of the day that supplants the prose-poetry of the “yellow” newspapers. In the post-Nixon era, we have seen something similar: the elemental force of opinion-based TV totally supplanting the politics of newspapers and conventional “evening news” programs. Trump is the ultimate result of this trend, not just because he, himself, is so obviously immune to any kind of printed matter but because the movement he created has been trained to disregard journalism—and, by extension, truth itself—entirely.

It’s fitting that Ailes exits the stage at a moment so similar to when he entered, a crossroads of activism, turmoil, corruption and unrest that will almost certainly alter the political and social landscape of the decades to come. Let’s hope that Trump is Ailes’ requiem; that the cynical and corrosive manipulation of image and feeling to the detriment of reason and meaning is buried along with him.