Friday, November 24th, 2006

•

Horrorthon Posts

Here are a few extraneous points I wanted to make about zombies, Romero’s zombie movies, and the Dawn of the Dead remake.

1) I added this to the bottom of my review of Dawn of the Dead (2004) directly below, but I don’t think anyone saw it, so I moved it up here:

ADDENDUM II: Dawn of the Dead joins an impressive roster of fantasy/sci-fi/horror movies that follow the unwritten rule that, before the end of the world, the protagonist must fall asleep and re-awaken. Tom Cruise does it; Sarah Polley does it; Cillian Murphy does it. Sometimes it’s a full night’s sleep and sometimes it’s just a catnap, but it’s somehow necessary: you doze off, and when you wake up, everything’s different. You may not realize it yet, but the phonograph needle of the universe has skated off the edge, and the nightmare has begun in earnest. It’s a deeply Freudian, deeply primal motif that’s been serving the purposes of apocalyptic fiction for decades: the original Dawn of the Dead begins with Fran waking up against a wall of blood-red carpet with an associate (also awakening) uttering the movie’s first line: “I’m still dreaming.” Examples: War of the Worlds (2005); Miracle Mile (1988); 28 Days Later (2002); 12 Monkeys (1995). Any others you gentlemen can think of?

2) I missed a cameo/homage in my first roundup (also below): the WGON helicopter from the first version makes an appearance right before the opening titles, in one of the nine or ten heavily-digital shots of Ana fleeing her neighborhood (right before she gets temporarily stuck behind the bus whose panicked driver attempts to take her car from her). Look!

WGON helicopter

I hasten to add that I missed this more than once: it took the director’s commentary for me to catch on. (You can see the heathaze and fumes coming off the helicopter in the new shot, which corresponds to footage I’ve seen of helicopters filmed from above: I point this out only by way of admiring the work done on the digital helicopter. That’s a hell of a lot of effort just to create an homage that even I missed twice! Way to go, guys.)

3) Thinking about the Zombie Rules and the question of whether they change from Romero to the new movie, I suddenly realized that I can’t think of a single character in any of the Romero movies who dies a non-bite-related death and then comes back as a zombie (Unless you count the very first zombie in the graveyard in Night, but we don’t really know anything about him, do we?) Ignoring that zombie for purposes of argument, every other character who becomes a zombie gets bitten by a zombie (including Stephen in the elevator, above) so it might as well be the new rules. I’m not sure what I’m getting at, but the 2004 zombie plague spreads about ten times faster than Romero’s zombie plagues, and this may have something to do with a) the new fast zombies as well as b) yes, you have to be bitten, but (as octopunk pointed out before) how close are any of us to hospitals, morgues, funeral homes, graveyards etc. anyway?

4) Kyle Cooper, oft-imitated but never-equalled film design guru extraordinaire, did the opening title design for 2004’s Dawn of the Dead. He’s the guy who did the titles to Se7en (which was his first claim-to-fame); He’s done a number of title sequences in this style before, so I was glad to discover that they went and got the real McCoy for this movie.

5) Octopunk and I have had a few conversations about the intriguing inverse relationship between the enjoyment levels on either side of the movie screen. With sci-fi and horror movies specifically, the worse things are for the characters in the story, the better they are for us, watching the movie. Trailers for upcoming summer movies understand this and work like travel brochures in reverse: they keep tantalizing you with how BAD things are in the place they’re talking about. The final “stinger” shot in the trailer is usually something truly, deeply awful like the tanker truck slamming into the windshield (and your face) in Twister or the Alien drone moving its head to nuzzle Ripley’s in Alien 3.

So, along those lines (bad=good) I think it’s fair to say that the true charm of the zombie threat is that it’s just way, way worse than anything else. I refer you to my comments about the “automatic end of the world” below; when I was discussing zombie movies with a few friends who were over at my house the night before Thanksgiving (to look at the balloons) and we watched the openings of both versions of Dawn of the Dead, I said, “Against vampires, you’ve got a chance. Against Aliens [Scott/Cameron/Fincher] you’ve got a chance. Against ‘body snatchers’ [e.g. “pod people”] you’ve got a chance. Against “the machines” [Terminator or Matrix] you’ve got a chance. Against “Martians” [H. G. Wells] you’ve got a chance. Against zombies…forget it.” When we got back from the title sequence and Ving Rhames was holding the shotgun on Sarah Polley, we agreed that it was clearly game over already.

There are some interesting ideas here, I think. Why are they so damned unstoppable, especially given that they don’t have amazing powers (like vampires) or super-advanced technology (like the machines) or the ability to blend in (like pod people)? I can think of a couple of reasons. First of all, unlike other threats that take over the identities of the good guys, the zombies do this very quickly and indiscriminately. Remember how Veronica Cartwright came outside and noticed that pods of Donald Sutherland and the others were forming, and woke them up (thus cancelling the lengthy pod-forming process)? Major setback for the pods, right? (Because they were creating duplicates, which is apparently a painstaking job.) Well, had those been zombie bites instead of pods, forget it. It would have only taken a few minutes (Romero) or a few seconds (2004) for the protagonists to be permanently out of the game (or rather, playing for the other team).

So speed’s important and communicability is important but what’s most interesting about the zombie threat is something that octopunk hinted at with his phraseology about how the zombies “get the upper hand and never lose it” (which implies a determined struggle on both sides): for such a deadly, unstoppable threat, they’re incoherent. Unlike every other threat I mentioned two paragraphs above, they don’t have any kind of master plan at all. They’re not trying to do anything per se, so they can’t be reasoned with or fooled or delayed or outwitted. The Warchowski’s “machines” used us for food, too, but their technique for doing so was very sophisticated, and, unfortunately for them, allowed a narrow window of human consciousness and tactical breathing room (the “matrix”) in which we could mount a subversive rebellion and inculcate a subsequent military revolution out in the real world. Vampires get fixated on individual prey or get overcome by hubris and make mistakes. The aliens will be canny; they will negotiate with Ripley (“Tell those drones to back off or I’m torching the eggs”) to even the odds; human ingenuity prevails. But the zombies are pure animal force; pure Darwin, and they can’t be reasoned with or out-schemed. So they take over the world, every time, as noted. It’s got to be an especially galling defeat, because losing to “the machines” or the body snatchers at least means there’s going to be something left that you can respect a little bit (“This is our time,” Agent Smith tells Morpheus), but the zombies just turn the entire world into shit irreversibly (as we see in the opening of Day of the Dead—nice “Brave New World” you guys created there…makes it all worthwhile), which makes them scarier and more deadly by an order of magnitude.

6) I went back and re-read “Home Delivery” by Stephen King (now that I’ve seen all the Romero) and I think it’s terrible. I stress that the outer space sequence is scary as hell and well done, but he should have just made up his own story and not grafted that idea onto Romero’s. I’m completely convinced that the one thing the zombie story shouldn’t have is a coherent explanation. It ruins it somehow. Besides, how much scarier is it if we just never find out what the hell happened? It seems much more realistic to me. (It must have taken a long time, in both Wells’ version and Spielberg’s, to figure out what suddenly happened to the invading aliens, even though the narrator understands immediately.) So “Home Delivery” combines a needless explanation, a mediocre retelling of the “zombies taking over, as seen on television” concept, and then a boring graveyard-shootout in a little island town. Yawn.

I can’t even think about zombies on an island now without going back to the extreme end of the 2004 Dawn of the Dead (which was added much later, in Los Angeles, when test-screening audiences objected to the suddenness of the “gunshot/blackout” ending. It’s like Schrödinger’s Cat, isn’t it? “Are you sure you want to see what happened?”). In the DVD commentary, the director etc. refer to the looming shadow through the mist in the camcorder footage by saying, matter-of-factly, “there’s Zombie Island” and not even discussing it, as if there was never any question for the filmmakers that the survivors were on their way, deliberately, to a place known as “Zombie Island.” They really should have stayed at the mall, if you ask me.

7) The opening of 2004 Dawn follows a specific pattern that I really like, which compares with the opening of Revenge of the Sith and the Bathtime at Clerkenwell animation: first you focus quietly on a SINGLE item (spaceship, singing bird, zombie) until you get the basic idea, and then you pull back or open a door or glide past the edge of a battlecruiser and suddenly see the entire thing. (Wouldn’t Sarah Polley and her husband have HEARD all of that shit going on outside their house? Helicopters; sirens; gunfire; burning houses and vehicles; car crashes; explosions; screaming—yet the bedroom is so quiet you can hear the tiles on the old-school digital clock flipping over.) It’s a great technique. The Romero movies get the idea across with verbal explanations, each time. (You don’t even understand the zombie in the 1968 graveyard until Ben explains it.) But the 2004 version teaches you what’s happening by showing you the husband’s instant tranformation so you can’t possibly misunderstand or get confused.

8) I quickly got tired of hunting down reviews of 2004 Dawn of the Dead because even the positive ones hasten to add the caveat that the new movie “lacks the depth/social commentary” of the original, which (they point out) was so shrewdly knowing in its equasion of mall-shoppers with zombies. I think that’s bunk: First, the new movie has plenty of “depth” of its own as I’ve noted; it’s about 9/11 and AIDS and CNN and consumerism and guns and other pertinent themes, and, anyway, there’s just no way to conclude that a story so primally evocative is without depth unless you’re looking for categorical excuses to dismiss it because of its formal identity as a bloody horror movie. (Apparently the original was “a satire,” which is news to me.) Where were all these critics when the original came out? The only review I can find from 1978 that praises Romero’s Dawn of the Dead is by Roger Ebert, who basically gets it right. Being on the cultural vangard is easy when it’s twenty-six years later; it’s getting things right at the time that’s hard because you’ve got to think for yourself, and not mindlessly follow the herd in search of sustenance, like a…well, never mind.

That’s it for now! Truly outstanding material all around. Happy Thanksgiving!

Wednesday, November 22nd, 2006

•

Horrorthon Posts / Horrorthon Reviews

Well, this was the dessert course that nobody expected, wasn’t it? A big slice of cappucino cheesecake sent over compliments of the chef and on the house—with brandy, espresso and a Cuban cigar. Yeah.

For me, these zombie movies turned out to be a roundabout re-introduction to what makes right now, the present moment, such a great time in the history of movies. To go from the doldrums of the mid-eighties—a time during which, in my opinion, everybody did their worst work (Garry Trudeau, Woody Allen, Elvis Costello, everybody)—straight to 2004 (beautiful, digital 2004) was an exhilarating reminder of how far movies have come. The technical artistry and visual sophistication that goes into even a mid-budget, B-list-actor horror movie like this is so stunning, so far beyond anything possible in the previous decades that it boggles the mind. Additionally, the de rigeur collection of “average” people in each film reveals something interesting about the modern era—at least on film, a randomly-selected group of Americans (and, by extension, the audience watching and grooving on them) are many degrees smarter, more sophisticated, more culturally savvy and just cooler than their counterparts in the previous decades’ films.

Summerisle called Romero’s dismissal of this movie “sour grapes,” but I think it’s more than that. On the 1978 Dawn of the Dead DVD commentary, Romero and Tom Savini talk at great length about how they disapprove of CGI and don’t like digital film in general. They make a lot of arguments about how it’s not “natural” and how CGI “throws you out of the movie” (all of which remind me of Bob Dylan—not the sharpest knife in the drawer—talking in 1987 about how he disliked “unnatural” audio CDs). Watching revered directors like John Schlessinger try to make modern thillers (Ronin) reinforces the argument that the art of cinema is just moving forward at great speed, leaving older artists and their talents behind. (The only ’70s director who has managed to fuse the best of his ’70s sensibility with the cutting edge of today’s film techniques is, of course, the man himself, Steven Spielberg.) So, I agree with Summerisle that this movie marks a fundamental advance over the original, and, more significantly, a movie that Romero himself could never have made.

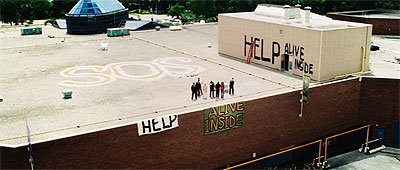

So it’s the end of the world and zombies are taking over (with the threat spreading out subjectively from the characters’ experience, as other reviews have noted) and the material available on television and in the montage that frames the opening titles quickly make use of the best techniques available for conveying the magnitude of the crisis: from Romero’s black-and-white television with the man in the horn-rimmed glasses explaining the “civil unrest” (in the ’60s, when “civil unrest” was actually something people talked about), we’ve come forward thirty-five years to the CNN era and a wobbly Betacam showing a press secretary in front of the Capitol Building flanked by secret service machine-gunning zombies. Nurse Sarah Polley and cop Ving Rhames run through a ten-minute “mini-28 Days Later” (evading the new, FAST zombies) and end up in a shopping mall, where, once again, the walking dead surround the entrances because “this was a special place to them” and, once again, it’s the perfect place for a showdown: us vs. the walking dead (and, once again, we lose).

The end of the world 2004-style hits an American population that seems considerably more ready for it. There are those who say that The Two Towers and Attack of the Clones (and Revenge of the Sith) are commenting on the Iraqi war; I tend to agree, and, along the same lines, the Americans in the new Dawn of the Dead face the global disaster with a hardened, knowing resignation and fortitude that obviously has something to do with these times we live in. (Our generation has its own uneasy relationship with the literal, biblical Apocalypse as well; the characters were obviously already thinking about the “End of Days” even before the zombies hit.)

I compared zombie movies to vampire movies before, but there’s a crucial difference: call it the “Kenny factor” or the “Aeon Flux” factor. What can this possibly mean? Basically that, unlike vampire stories, which run the gamut from a single Vampire and its direct spawn (Dracula) to an entire town (‘Salem’s Lot) to larger populations (Blade), the zombie story always involves a threat that grows without boundaries, as long as there are people dying anywhere, so, ergo, “zombie story” = “world overrun by zombies” no matter what. There’s just no such thing as a “limited” zombie story; the world dies each time, like Kenny in South Park or Aeon Flux in her early animated adventures. Romero understood this and never bothered to try to tie his various stories together as one narrative; he just comes in at a later stage each time: we see the beginning of the catastrophe that ends the world in 1968 and then the middle of the catastrophe that ends the world in 1978 and then the end of the catastrophe that ends the world in 1985; the world just ends, over and over, each time, like Kenny’s death, because the zombie story itself is a one-of-a-kind yet endlessly repeating fable that applies to each era with equal force.

The group of survivors who gather here are likable and interesting, and, more significantly, deal with their differences of opinion rather quickly and efficiently (for a change). As I said above, they seem smarter than their counterparts in earlier zombie movies (they’re certainly more tolerant of each other and more innovative). In fact, everything happens with a speed and economy that’s tremendously refreshing after the shambling chaos of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s versions. The speed of the story has its drawbacks: the one thing I feel this movie lacked was a coherent framework for depicting the horror of good people turned into bad zombies; in each case it all happens so fast (death-awakening-snarl-headshot) that there’s no time for anything like the woman in the tenement who embraces her dead husband only to have him sink his teeth into her shoulder. But the business with Matt Frewer and the ending on the dock more than made up for that.

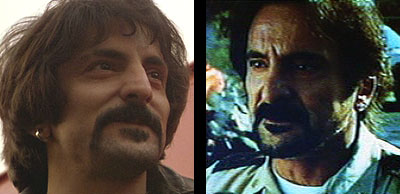

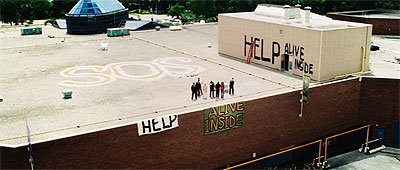

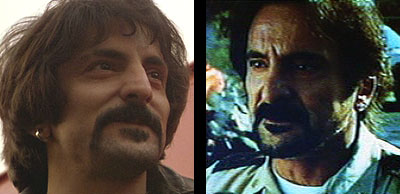

And how about those homages/cameos? Look!

Tom Savini

Scott H. Reiniger

Ken Foree

Gaylen Ross

BP (A Qualpeco Company)

Yes indeed, it’s the details that count. Speaking of details, Summerisle went bananas over the Andy tape (which I haven’t watched yet) but holy shit, did you guys watch the fucking closing credits? The camcorder “found on the boat” with old footage on it? The movie ends like the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter”– you fade out in with reasonably presentable set of conditions, assuming the best, and then peek behind the curtain to watch it all fall apart “after” the ending. That horrible boat ride…and the island of zombies…and the camera’s still running…my God, it’s good. (If you freeze frame in the final burst of video static, you can catch a few frames of two bimbos kissing from the tape’s original content as the camera heads skip until you’re back with the zombies advancing on the lens.)

A fine piece of work all around. And I think I’m pretty much “zombied out” for now, but man, what a ride! Now I’ve got to go watch Howard’s End or something to cleanse my palette.

ADDENDUM: They changed the rules, didn’t they? Only zombie-bite-victims get zombified? I hope I’ve got that wrong, because it screws up the premise. (How could it start without corpses rising from the grave?)

Tuesday, November 21st, 2006

•

Horrorthon Posts / Horrorthon Reviews

Very clever indeed. This definitely kept me guessing until the end, and (unlike its predecessor) was put together with a cinematic flair that actually justified a lot of its more garish features (like those stacatto montages that octopunk complained about so hilariously). I’m glad somebody decided to just write James Wan a check, thank him kindly, and then escort him from the premises and bring in a professional director, because the filmmaking is much snappier and more alert and the difference is clear immediately.

The Saw movies (so far) are fun but don’t have much depth, which is too bad, since they’re overtly trying to convey an idea. I don’t necessarily agree with octopunk in his scathing dismissal of Jigsaw’s purposes and methods: the man has a sadistic streak, obviously, but his underlying thinking is reasonably sound, in my opinion. In round two, his “traps” lack the precision and clarity of the ones we saw last time, but I think that’s clearly because you’re supposed to zoom back to a wider view and understand the grotesque trick that he and his new protégé are playing on Detective Matthews.

(We don’t do “spoiler warnings” here on Horrorthon, right? I certainly hope not, because I’ve been “spilling the beans” left and right.)

As I mentioned, I don’t believe these movies to have much depth, which is why they tend to evaporate in the mind like bloody cotton candy mere hours after you’ve seen them. I think the real problem is a rather insurmountable debt to David Fincher (which Saw can’t overcome any more than countless sci-fi movies like Outland and Event Horizon never migrate beyond the margins of the Ridley Scott material they’re mimicking). Octo pointed out that Saw is built out from the Tyler Durden gun-to-the-head sequence in Fight Club; this film draws its entire essence from the final twenty minutes of Se7en, which is too bad, because (just like Peter Hyams is no Ridley Scott) these people are not Fincher, and cannot imbue the material with the same majestic savagery and existential nihilism as Fincher’s movies have.

The comparison is especially unkind to Donny Wahlberg, who, I think, is very good in the movie, but he’s burdened with the problem of not being Brad Pitt, who (as I’m saying) already played exactly this role and did it so well that nothing Wahlberg does can possibly eclipse Pitt’s searing performance. (“What’s in the box?“) Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery and all that, but there’s only one Brad Pitt and Wahlberg ain’t him.

Other points:

1) As good as Wahlberg is, Dina Meyer is awful. She’s obviously kept herself sharp-faced (as all Hollywood women must) but she’s no better here than she was in Starship Troopers and her huffa-puffa acting weakened her sequences considerably.

2) Some of the traps don’t make sense. I lost track of all the hidden syringes; we never find out what’s in the first safe (“What’s in the safe?“); the concept of piecing together a lock combination from seven or eight digits makes no sense (there are a million permutations); nobody takes the antidote; the big huge guy turns into a raving maniac and stops making any sense (his desire to kill the others is incoherent); and, in general, the scheme lacks the precision of the similar business in the first movie.

3) Like I said, the “twists” are terrific.

4) With the exception of Ms. Meyer, all the actors are good. I particularly liked Glenn Plummer (“the black guy”) but I’ve liked him ever since Speed. Also, the Italian-looking girl is hot.

5) I forgot to mention Cube, another movie that this one resembles.

6) What’s the point of the oven trap? What can you possibly do besides get inside and get cooked? And what was the deal with that fantastic graffito of a smirking devil next to that valve? Or am I missing the point entirely?

7) Somebody is going to have to sit me down and explain in simple terms what the hell the deal is with the room in Part I. Why is the guy who wrote the movie dead and mummified in there? I thought he prevailed in the end (and the script wasn’t that bad!). Why is there another dead body in the center of the room? Why does everybody end up getting into the bathtub?

I’m picking on the movie but I certainly found it watchable and engaging. You have to understand I’m not used to the “torture film” genre (if there is such a thing) so I may be expecting more than can be delivered. I’m definitely looking forward to the third one (although I’ll miss Tobin Bell) and I have to give the franchise credit for intelligently piecing the chapters of the story together. Fun stuff, like I said, but fairly weightless, and less intellectually engaging than it might have been in the hands of more accomplished artists.