Tuesday, August 11th, 2015

•

Writing

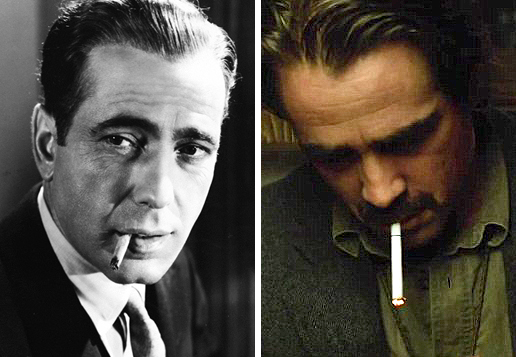

Now that it’s complete, the second season of HBO’s True Detective can be properly judged, and, I think, elevated to its rightful status: a noble experiment at worst and, at best, an erudite and deeply-felt reaffirmation of the ninety-year-old Noir tradition that’s threaded through our literature, movies and myth. At the very least, Season 2 deserves to be assessed as a whole, given its novelistic structure and grandiose thematic and narrative ambitions—considered piecemeal, the individual parts have elicited scorn and derision that they tended to deserve. The early episodes, in particular, were disastrously weak; had they been book chapters, any competent editor would have demanded that they be rewritten. (Re-watching the premiere, I was astonished at its plodding, pretentious clumsiness, especially in comparison to the story’s thrilling, tragic final hours.) But now that we have all the pieces, the puzzle fits together into a surprisingly rich and satisfying picture—Nic Pizzolatto’s grim, intricate eight-part crime saga was an extraordinary overreach that, in the end, conquered a surprising and impressive amount of the vast territory it claimed.

Of course, from the beginning Season 2 suffered in comparison to its predecessor, which was a home run of Babe Ruth proportions—the chemistry between leads Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey and (in McConaughey’s case) the once-in-a-lifetime alchemy of a perfect match between actor and character elevated “Rust Cohle” to instant, iconic immortality. Season 1 had none of the hesitance and awkwardness of its successor—the unspooling of consecutive Louisiana murder investigations (expertly framed by an Internal Affairs probe a decade later) was so suspenseful from the moment it started, its dense philosophical cohesion so indelibly rich, that all subsequent disappointments (including what many considered a stunningly anticlimactic and unsatisfying denouement) were forgiven or overlooked.

The arrogant neo-Nietzschian figure Pizzolatto’s cut—his grandiose pronouncements and tendency to sneer at his critics—didn’t help: when Season 2 stumbled out of the gate, it was easy to cast him in the hubris/nemesis template of Michael Cimino or M. Night Shyamalan (both of whom followed up extraordinary debut successes with disastrous pratfalls like Cimino’s studio-sinking Heaven’s Gate). After the first episode of the new season, I was convinced (along with nearly everyone else) that we were witnessing just that sort of harder-they-fall comeuppance. But things changed—by the time the story had performed its unexpected 66-day time jump (after the show-stopping massacre that ended Episode 5) it was clear that the deep historical and artistic roots of this vast Los Angeles tale—and its ravenous need to devour every conceivable Noir archetype—were bearing strange, rich fruit: a modern-yet-ageless detective story that can stand alongside nearly any previous attempt to master the genre.

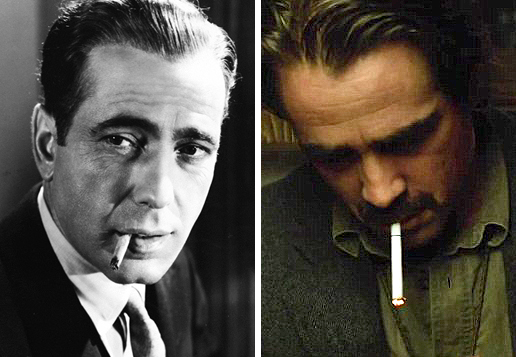

Noir is less about film than literature—it actually begins with Ernest Hemingway. After his WWI novels The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1927)—in which the moral chaos and vertigo of wartime are examined both on and off the battlefield—Hemingway explored the darkness of peacetime in To Have and Have Not (1937), a crime story built along a Marxist armature that (largely thanks to Howard Hawks’ 1944 Humphrey Bogart/Lauren Bacall movie) has been retroactively cast as the beginning of Noir. In “Hemingway and his Hard-Boiled Children” (1968), literary essayist Sheldon Norman Grebstein credits Hemingway with inventing a worldview in which

Crime is the specific social equivalent of war, and its prevalence signifies that no watchful deity and no meaningful pattern of order rules over man. The overwhelming impression derived by the reader of Hemingway is that of a violent world, a world at war, a world in which anarchy prevails. Hemingway’s depiction of violence, although it is in frequency by no means his major concern, is nevertheless perhaps the most vivid and memorable aspect of his art. And even where there is little or no violence, as in The Sun Also Rises, we are given the sense of breakdown, fragmentation, disintegration. In such a world, toughness seems the only means of survival […] Throughout Hemingway’s early work, and despite the keen social consciousness of most of it, law neither guides human conflict not seemingly has much relevance to it. No characters in modern fiction exercise greater moral awareness than Hemingway’s; none struggle harder for moral certainties; and almost none achieve such little success.

Hemingway’s stylistic successor was Dashiell Hammett, a former private detective who (along with Raymond Chandler, a decade later) debuted in The Black Mask, a pulp magazine launched by august literary critic H. L. Mencken (working with drama critic George Jean Nathan) in 1920 for the express purpose of making money with cheap crime stories in order to support Mencken’s more high-toned publications. The stripped-down style of Hammett and other “hard boiled” writers was not held in high regard: Herbert J. Muller (in his exhaustive 1937 study Modern Fiction) sneered that “this ‘cult of the simple’ appears in various forms in the modern world [including] the ‘hard-boiled school’ […] It is usually a sign of surface restlessness, a craving for novelty or thrill—the popularity among the sophisticated readers of novelists like Dashiell Hammett is more a fad then a portent.” But Muller allowed that “it also represents a serious effort by some intellectuals to find happiness in the mere being or doing of the great mass of common people.” And others acknowledged the importance of Hammett’s stylistic advances: Chandler wrote that Hammett had a style “but his audience didn’t know it, because it was in a language not supposed to be capable of such refinements” – Hammett was “spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

It took decades for Hammett’s crime stories to be accepted into the literary canon, since their clean, spare surfaces and tawdry subject matter disguised their artistry. As critic Phillip Durham wrote in “The Black Mask School” (1968), “The idea that style is the American language—discovered independently by several writers in the hard-boiled genre—is unquestionably one of the most significant aspects of the evolving, hard-boiled tradition. Style, then, is where you find it: not restricted to the drawing room or study, but equally discoverable in the alleys […] Hammett went to the American alleys and came out with an authentic expression of the people who live in and by violence.” Hammett’s best work—the landmark novels Red Harvest (1927), The Dain Curse (1928), The Maltese Falcon (1930), and, especially, The Glass Key (1931), operate like Hemingway’s crime saga in presenting a world with no natural moral order; a narrative environment in which boundaries between the light and the dark are hopelessly blurred and the detective and criminal are both cast adrift, groping for right and wrong. According to Hammett, The Maltese Falcon’s protean hero Sam Spade (best remembered via Bogart’s onscreen portrayal ten years later) “had no original…He is a dream man in the sense that he is what most of the detectives I worked with would like to have been: a hard and shifty fellow, able to take care of himself in any situation, able to get the best of anybody.”

Raymond Chandler is to Hammett as William Faulkner is to Hemingway: a baroque, romantic alternative to the ice-cold modernism of the early “hard-boiled” style (in fact, Faulkner himself wrote the script for Howard Hawks’ 1946 movie of Chandler’s 1939 novel The Big Sleep – and Bogart, again, embodied the central role; if Sam Spade was Bogart’s Indiana Jones, The Big Sleep’s sardonic Phillip Marlowe was his Han Solo). Chandler exchanged Hammett’s lonely Edward Hopper minimalism for a dizzying, lush complexity – and, more important, abandoned Hammett’s abstracted cityscapes (like the Hobbes-inspired “Personville” of Red Harvest) for the poisoned sprawl of Los Angeles, permanently affixing the Noir tradition to that city. As Herbert Ruhm argued, “Chandler is indisputably the best writer about Urban California […] [He] succeeds as no one else has succeeded in portraying Los Angeles, including Hollywood, and it seems at times that it is neither the violence nor the solution of the mystery Chandler is interested in as it is the city and the people.” “Mr. Chandler,” W. H. Auden wrote in 1962, “is interested in writing, not detective stories, but serious studies of a criminal milieu, the Great Wrong Place, and his powerful but extremely depressing books should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art.”

Noir migrated from page to screen in the 1940s, where the simplified scenarios meshed perfectly with wartime frugality (the movies were famously underlit to save set-building costs), but the primal, nihilistic thrust of the original stories got blunted by Hollywood: John Huston’s earnest retelling of The Maltese Falcon (1941) distorted and cleansed the novel’s essential ruthlessness (and cast girl-next-door Mary Astor as the book’s terrifying femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy—a role that calls for an Angelina Jolie). Hammett would not get adequate cinematic treatment until decades later, when the Coen brothers smelted Red Harvest and The Glass Key into their stylistic breakthrough Miller’s Crossing (1990). (Red Harvest also inspired Kurosawa’s 1961 Yojimbo, which was itself remade first as the 1967 Sergio Leone/Clint Eastwood classic A Fistful of Dollars and again as Walter Hill’s 1996 Bruce Willis vehicle Last Man Standing.) The brutality and moral chaos of Noir – the Hemingway vision of a senseless world, viewed through the lens of California crime stories – had largely vanished from movie screens by the late 1960s, when Pauline Kael famously identified the “Urban Western” (starting with Dirty Harry and continuing through the Lethal Weapon series) as the new template for cop movies—a safe, Manichean world of vigilante heroes who “go rogue” in order to uphold and restore a moral order, like the Arthurian figures of Old West legend.

But despite superficial, essentially fraudulent camp pastiche like Body Heat (1981), Dead Again (1991) and The Usual Suspects (1995), the central Noir ideas have survived cinematically, through occasionally-successful recreations like the period-pieces Chinatown (1974) and L.A. Confidential (1997) and fringe experiments like William Friedkin’s slick, nightmarish To Live And Die in L.A. (1985), James Foley’s striking Jim Thompson adaptation After Dark, My Sweet (1990), or the stunning extensions of the L.A. Noir concept into science fiction (Ridley Scott’s visionary 1982 classic Blade Runner), surrealism (David Lynch’s astonishing triptych of 1997’s Lost Highway, 2001’s Mulholland Drive and 2006’s Inland Empire), Warholian Pop-art pastiche (Who Framed Roger Rabbit, 1988) and even computer games (Rockstar’s innovative 2011 L.A. Noire). Novelists like Walter Mosley, James Ellroy, Thomas Pynchon (whose 2009 postmodern Los Angeles neo-Noir shaggy-dog-tale Inherent Vice was just brilliantly translated into celluloid by Paul Thomas Anderson) and Cormac McCarthy (who skated completely off the deep end of reheated Noir philosophy with his debut screenplay for last year’s disastrous The Counselor) still can’t resist the lure of the Los Angeles crime story and all of its gaudy opportunities to meld the lowest human behaviors with the highest existential philosophy.

Drunk with hubris, Pizzolatto chose to take all of this on at once, and the result has been maddening, frustrating, impenetrable, inept, uneven, rushed (both in its execution and unmistakably in its conception and production) – but, finally, remarkable: as pure and unalloyed a resuscitation of the hybrid literary/cinematic Noir tradition as has ever been attempted. The dizzying, numbing complexity (Faulkner was asked to explain a mysterious dead body that appeared halfway through The Big Sleep and was never mentioned again; baffled, he contacted Chandler, who had forgotten the whole thing); the vast, cynical corruption of all public and private institutions; the endless booze and drugs and cigarettes; the dizzying, hallucinogenic sprawl of the city and its hapless, damned inhabitants; the moments of fragile and delicate sentiment and nobility that are mercilessly crushed and forgotten; all the decades-old elements of Noir are not just reconstructed but are blown up to epic, mythical proportions—Pizzolatto does to Los Angeles what Leone did to the Old West, expanding its scope and scale beyond any journalistic depiction of reality, so that the primal human elements of darkness and chaos, justice and sacrifice are cast in vivid, operatic relief. We have a parched city that needs water (as in Chinatown); a shortage of busses contrived to subsidize a rail system (like the freeway-based conspiracy in Roger Rabbit); contaminated land; lethal desert showdowns; prostitution rings; sabotaged investigations; and, finally, broken and maimed protagonists propelled past the limits of the public institutions that have failed them and their own faltering endurance, into an endgame where they must stand or fall based on nothing but whatever shreds of decency and grit they can muster. The modern touches—e-cigarettes; GPS transponders; Blackwater-style mercenary groups; Russian mobsters; TMZ exposés; sexual harassment charges (and the resulting “sensitivity training” requirements); ankle monitors; Viagra and MDMA; memories of the 1992 riots—not only don’t interfere with the eternal Noir elements but actually enhance their potency: the characters’ apprehension that they’re living out an unchangeable template—that they can’t escape the “world they deserve”—lends a fatalistic nuance to the story. (“Some of these sheds have been here since the 1930s,” the state attorney notes as the detectives finally find the remote murder scene.) When Bezzerides’ father tells Velcorro that he “must have lived a hundred lives,” he could be referring to the archetypes that stand behind his character, and the dozens of writers who have mapped out this dark territory—the story that “will never blow over”—down through the decades.

But, in the end, True Detective Season 2 was Pizzolatto’s own—and the circumstance of his empowerment as dictatorial auteur, as lone author, allowed the creation of a flawed but unique work, as far away from the focus-tested and homogenized Hollywood product of the day as could be imagined. Pizzolatto took on the authorless expanse of Los Angeles, and the countless attempts to impose identity onto its endless baked landscape—through lineage, through ownership, through crime, and, as in every Noir tale, through the struggle of the detective—and, mostly, succeeded in making his mark. Velcoro and his “hundred lives” are the repeated images of the same primal figure, Hammett’s “dream man,” a grizzled, timeless hero who transcends the specificity of any author or decade, whose hopeless struggle against the rotted fabric of this vast, haze-covered city is the same every time—he has a name, but, as Leonard Cohen whispers, never mind.

Friday, July 24th, 2015

•

Politics

I had not watched Donald Trump’s July 8 interview with NBC News’ Katy Tur when I posted my (clickbait-titled) Trump is Hitler post on Tuesday. (I admit that I have actively avoided viewing Trump footage, in general, over the years—I am, for example, unfamiliar with his TV show about firing people.) But now that I’ve been through all 29 minutes of this particular sparring match, I’m compelled to double down on my contention that he really is reproducing the German dictator’s early tactics (say, 1922-1930) move for move.

It should go without saying that Trump is not doing this deliberately—he is not a neo-Nazi or a white supremacist—nor is he aware of the correlation, or even possessed of the wherewithal to understand the base mechanics of fascism (or even of government). But then, Hitler started out with the best of intentions, too: he simply wanted to save his beloved country from what he perceived as fatal internal weaknesses—of elected officials and, more urgently, people of a certain ethnicity, just like Trump—and, also like Trump, he was anxious to reinvigorate the armed forces for these and other purposes (“I’m more into the military than anybody,” Trump avowed in the NBCTV interview). Except in fiction, nobody sets out to be an instrument of bloodshed, poverty, social destruction or institutionalized injustice; nobody desires the role of destroyer (at least not consciously; Freud might say otherwise).

As I have already learned firsthand in the wake of my previous post on the topic, the comparison seems, to many, outlandish at best—Donald Trump, surely, is a figure of fun and his wild rhetoric and climbing poll numbers cannot be taken seriously. But make no mistake: this is not a joke, and should not be dismissed. “The idea that Trump’s appeal isn’t genuine,” Eric Boehlert of Media Matters cautioned two days ago, “or that the press has lured Republicans into supporting him is likely more comforting than acknowledging the truth: Trump, an ignorant, nativist birther, is appealing to an often-ugly streak within the conservative movement.” Disputing the dismissive language with which Trump’s ascendency has been reported, Boehlert stresses how “Fueled by hateful rhetoric and right-wing media programming, Republicans and conservatives have veered towards extremism in recent years. If the press had honestly documented that trend, today’s Trump phenomenon wouldn’t come as such a shock.”

Watching Trump interviewed at length (which, I freely admit, I should have done earlier) is extremely illuminating. Reading his quotations in the context of campaign-related news accounts does not do him justice—you need to see him to get the full effect. Clearly, it’s an effect that is as pleasing and rewarding and fulfilling to many thousands of Americans as it is viscerally repugnant and appalling to you and me (when it’s not uproariously and inadvertently funny, which is how Jon Stewart and others outside Stewart’s comedy wheelhouse are—somewhat nervously—choosing to regard it). You need to see Trump because the real force of his rhetoric doesn’t come across without the sound and the visuals: the coarse, accented voice; the ugly diction; the boardroom posturing; the glowering facial expressions; the spray-tan; the awful neckties and suits; the sneering condescension; the hair (which Trump knows is ridiculed, and affably defends: “My hair is just fine,” he insists). You can’t understand what’s happening until you look closely at this caricature of grotesque hubris and understand that precisely the elements from which you recoil are the ingredients of his stunning popularity.

Of course, I’m talking about class—not erudition or intelligence or political posturing or decorum, or wealth, but pure social class, the great American taboo subject. “Although most Americans sense that they live within an extremely complicated system of social classes and suspect that much of what is thought and done here is prompted by considerations of status, the subject has remained murky, and always touchy,” the late literary historian Paul Fussell wrote in his landmark study Class (1983): “Since I have been writing this book I have experienced the truth of R. H. Tawney’s perception, in his book Equality (1931): ‘The word “class” is fraught with unpleasing associations, so that to linger upon it is apt to be interpreted as the symptom of a perverted mind and a jaundiced spirit.'” Fussell elaborates, “At the bottom, people tend to believe that class is defined by the amount of money you have […] Nearer the top, people perceive that taste, values, ideas, style and behavior are indispensible criteria of class, regardless of money or occupation or education.” Elaborating on details of lower-class dress and grooming that he feels are actually intended to offend finer sensibilites (such as garish baseball caps or “legible” sweatshirts), Fussell concludes, “[dressing this way] says to those whose expensive educations have persuaded them that the ideal of dignity is the Piazza San Marco or the Parthenon or that the ideal of the male head derives from Michaelangelo’s David or the Adam of the Sistine Chapel: ‘I’m as good as you are.'” Fussell, I’m sure, would have instantly understood the basic meaning of Donald Trump’s candidacy: Trump’s enemy—his supporters’ enemy—isn’t Mexico or illegal aliens or ISIS or Muslims. It’s the American upper classes; the elite.

The overarching forces of American Conservatism—banks, corporations, business lobbies, energy consortia, the “military-industrial complex,” and the entrenched dynasties entwined with these interests—have done a masterful job over the decades of disguising themselves so as to ingratiate with the weakest and most ordinary amongst us: the simple, unassuming (white) workers and strivers; the downtrodden and oppressed (white) rural Christians; the bolo-tie wearers; the (white) truck drivers; the poor, struggling, honest, ordinary (white) people who didn’t go to fancy colleges and don’t live in big cities and advance fancy-sounding “European” (“socialist”) theories about how hard-earned dollars must be given to “urban” (black and hispanic) “moochers.” Through precise manipulation of (mainly Church-related) cultural imagery, and a crafted mythology of pioneering “small-businesses owners” who can succeed through honest toil, a legitimately elite contingency has managed to bond with its inverse demographic—to compel trailer-park residents and welfare recipients to look at, for example, George W. Bush (as pure a representative of extreme patrician wealth and its interests as has ever crossed the national stage) and say, “He’s like me; he’s on my side.”

On these terms, the failure of the Republican candidates in the last two national elections makes perfect sense. McCain was supposed to be a “salt of the earth” war hero, an independent Gary Cooper type (despite his nepotistic military career), but it turned out that he was mainly popular with the Washington D.C. press corps; nobody else liked him. The desperate gamble to re-up McCain’s cultural-underclass credentials by adding Sarah Palin to the ticket not only failed: the tactic revealed the panic involved; the awareness of the slipping mask that needed to be more strongly affixed. And Mitt Romney was a similar compromise-candidate whose “competence” (meaning, personally generated wealth) and reassuring Midwestern squareness were trusted to inspire confidence despite his peculiar mundanity—unlike Bush, he could not quite make himself come across as a regular joe, but he was nevertheless expected to appeal to voters by embodying that most hallowed of Randian archetypes: the successful, attractive “self-made” business titan (as if he were Henry Ford, if Ford had made foreclosures and layoffs rather than cars). Romney was genuinely predicted (by vast crowds of white Americans) to win handily, but, unfortunately, the outsourcing and the liquidation and the overseas factories were more visible and more toxic than Republicans apparently realized, and—most famously—the jig was up when a waiter’s phone camera told the real story of the contempt behind the curtain.

And that’s where Trump comes in. The voters who liked George W. Bush because he “owned” a “ranch” in Crawford Texas* and mispronounced “nuclear” and behaved like a drawling Texas good old boy (even though he was born in New Haven, Connecticut, attended Phillips Exeter Academy, was a cheerleader at Yale and graduated Harvard Business School) are now being presented with the real thing—a genuine vulgarian. The basic scam of Conservative American politics—the faux populism—is finally being exposed, because those carefully-groomed constituents trained to dislike “the elite,” taught to sneer at Obama’s putting Dijon mustard on hamburgers and John Kerry’s windsurfing and the Clinton’s million-dollar book deals and speaking engagements (one of the most incredible selective-example scams in the history of mass communications), are suddenly realizing that there’s no real difference (at least as far as class indicators go) between the top-tier representatives of the Left and the Right. (We on the Left, it almost need not be elaborated upon, do not have this problem because our ideology is built on respecting hierarchies of achievement and erudition; we don’t have to tie ourselves in rhetorical knots insisting that an Editor of the Harvard Law Review turned University of Chicago Law School professor is less competent or intelligent than a Hollywood B-movie actor from Eureka college who became a radio spokesman for General Electric or a Wasilla beauty pageant contestant who never read a book.)

Watching the NBCTV interview through this lens, it becomes increasingly clear that it is not the man’s ideas as much as the persona itself that appeals to his supporters—that precisely the traits that propel Trump off of any reasonable person’s radar are the ones that make him the Republican front-runner. It’s not the rhetoric, it’s the person they like, as evidenced by comments on the interview’s YouTube page:

We need someone who is good with money and stands up for himself like DT

He will turn America great again.

[He is winning polls] Probably because he’s upfront and honest about his opinions. Most politicians simply put up lies to garner votes.

Please spread the word around your communities. I genuinely think this man can help your people and ALL of us as well. He is right we are getting screwed. We ALL should be able to prosper in this once great nation that in my opinion will always be great. Even in our darkest hour we are better then the rest.

And when you then look at what Trump is saying (for example, about how he would conduct Middle East foreign policy) the juxtaposition is suddenly not funny at all:

TRUMP: With ISIS, you kill them at the head—you take the oil. That’s where they’re getting their money. If you bomb the hell out of it, you bomb the hell out of it. You’ve got to stop their wealth; they’ve got tremendous wealth.

TUR: What about civilians?

TRUMP: I’m talking about oil. I’m talking about oil areas. I’m not talking about civilian areas.

TUR: Civilians are near oil areas.

[pause]

TRUMP: Oh, give me a break, Katy. Go ahead, next question.

All of this—the establishment disdain (which is entirely mutual); the underestimated populist fervor; the black-and-white rhetoric—is, as I’m saying, very familiar. As Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw wrote, “Many contemporaries made a mistake in treating Mein Kampf with ridicule and not taking the ideas Hitler expressed there very seriously”— through which, as Kershaw explains, “Everything could be couched in terms of black and white, victory or total destruction. There were no alternatives. And, like all ideologues and ‘conviction politicians.’ the self-reinforcing components of his ‘world view’ meant that he was always in a position to deride or dismiss out of hand any ‘rational’ arguments of opponents.” And Hitler, a “trooper with gypsy blood” (who appalled American supporter and Harvard graduate Ernst Hanfstaengl by “sugaring a vintage wine” during a visit) transcended and even exploited his Bavarian-peasant trappings: “He could have peppered [the wine],” Hanfstaengl wrote, “for each naïve act increased my belief in his homespun sincerity.”

Again, to be clear, I don’t believe that Donald Trump will be nominated or elected and I don’t believe he will rise in power to become a genocidal, warmongering dictator (despite his clearly-stated racist/interventionist views)—mostly because (as I wrote last time) the United States is a far more robust democracy than was the fragile Weimar Republic. But have no illusions: this is genuine demagoguery, which is working to expose a legitimate mass movement. Trump may prove harmless, but the dark and violent forces he is stirring—the fervent call to “make our country great again”—are very familiar and very real.

*It was not a functioning ranch and had been bought and donated by a church group shortly before his inauguration; once out of office, Bush sold it and moved to Preston Hollow, an affluent gated community outlying Dallas.

Tuesday, July 21st, 2015

•

Politics

I’m sorry but this is exactly what nascent, doctrinaire fascism looks like. More timid comparisons (to George Wallace, to Barry Goldwater) are insufficient: Trump is following the Adolf Hitler template exactly. I don’t want to hear about “Godwin’s Law” when Bernie Sanders is called a Nazi in the National Review and Obama has been compared to (and directly portrayed as) Hitler at least as many times as he’s been called a Socialist or a Muslim; the taboo on the comparison should be retired.

We balk at the idea because Trump is so un-Hitler-like: he can’t be taken seriously; he’s “a clown” (even according to Fox News); he has no chances. But it was the same with Hitler. In late 1920s and early 1930s Germany, Hitler was “the ranting clown who bangs the drum outside the National Socialist circus.” As Andrew Nagorski, author of Hitlerland (2012), recently explained, “you had Americans meeting Hitler and saying, ‘This guy is a clown. He’s like a caricature of himself.’”

Trump’s message, exactly like Hitler’s, is blindingly simple: the public should feel justified in their suspicion that public institutions, despite their stated goals, have betrayed them—that they, the public, are being gulled by rhetoricians who cannot deliver on their promises because they function in a noncompetitive environment without penalties and, therefore, get away with nonperformance. Hitler spoke as a soldier, and Trump speaks as an entrepreneur, but they each frame the discussion in terms of a suspension of fairness: they are each saying, I have struggled to compete upon what I once believed to be a level playing field and have been sold out. For Hitler it was the treaty of Versailles; for Trump it’s Obama’s trade and immigration policies. The circumstances are vastly different but the sentiment is identical: if you, listening to me, feel that you’re not getting anywhere, you’re not alone—none of us are, because our leaders have failed us. The military and the business rhetoric are nearly identical, because both spheres operate (ostensibly) in terms of direct competition, of territory and (therefore) goods and wealth, power and influence won and lost directly through sacrifice and effort (as opposed to the empty gestures of politics). And, in both cases, the racial undercurrents of the argument seem to emerge naturally from the observation of the struggle: I can’t win, because somebody else is being given a break, unfairly, and the powers that be are letting it happen. It’s an incredibly powerful message, in either century, because it works to ennoble anyone’s frustration and envy: If things are not going your way, you don’t have to “suck it up;” you can fight back. You’re not alone; you don’t have to be embarrassed by or to hide your racially-based suspicions, because they’re correct. “Those people” are eating your lunch, and if you’re tired of concealing that certainty, you don’t have to conceal it any more.

This is why Trump always attacks not just politicians but newspapers, websites, and individual journalists by saying they lose money. (He’s been doing this since the early 1990s when Spy Magazine, after being described by Trump as “a failure” that “won’t be in business in a year,” gleefully started running its “Chronicle of Our Death Foretold” countdown calendar in each issue.) Today, responding to a blistering attack from the Des Moines Register (regarding Trump’s remarks disparaging John McCain), Trump (predictably) said, “The Des Moines Register has lost much circulation, advertising, and power over the last number of years.” In other words, you don’t have to listen to them because they can’t do their jobs—just as McCain couldn’t, when he was a soldier. (The fact that Trump dodged the draft doesn’t affect his argument—he’s directly challenging, not McCain’s bravery or ideology, but his competence in combat.) Hitler’s early triumphs, from the “Beer-hall putsch” (1923) to the remilitarization of the Rhineland (1936) were demonstrations not just of what could be done but of what Germans were being prevented, by their leaders, from doing—what their intrinsic competence made possible, as Hitler’s had, personally. Hitler spoke like a modern self-help guru—I did these things, and so can we all—and it’s the same kind of invigorating, “empowering” narrative that Trump is using today.

And, again, the racial subtext of the message (in either context) is not just clear but inevitable, since any hint of racially-based compensatory social measures (Affirmative Action, “political correctness,” “race-hustling”) can so easily be presented as thumbs on the scale; as an imposition of unfairness onto the lives of ordinary, struggling (non-ethnic) citizens. “The national community gained its very definition from those who were excluded from it,” Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw explains: “Racial discrimination was inevitably, therefore, an inbuilt part of the Nazi interpretation of the concept. Since measures directed at creating ‘racial purity’ […] exploited existing prejudice and were allegedly aimed at strengthening a homogeneous ethnic nation, they buttressed Hitler’s image as the embodiment of the national community.” As in the context of Nixon’s brilliantly toxic post-Southern-Strategy “Silent Majority” rhetoric, the listener need not feel alone or aggrieved; you finally have a champion who will say the things you cannot. As Josh Marshall explained, “Trump is running an angry, populist campaign focused on xenophobia and ‘I don’t care what you think’ aggression against ‘the establishment’ and ‘elites’ of all stripes. To think that trash talk against an establishment favorite [McCain], who is only marginally relevant to the politics of the moment in any case, will upset that apple cart is to thoroughly misunderstand the politics of the moment.”

To be clear: Trump will not be the nominee or the president. (And I’m sure he doesn’t personally harbor genocidal ideas or plans.) But the reason he won’t take power goes back to the decades-long debate about the roots of Nazism and the culpability of the leader vs. the people: our democracy, thank God, is not as weak (or young) as the doomed Weimar Republic, and our legislative and elective apparatus are not as correspondingly vulnerable to partisan tampering—we struggle with gerrymandering and voting-rights issues, but nobody can do the equivalent of dissolving the Reichstag (as Hindenburg and his cabinet did over and over, disastrously, in the 1930s, compelling the public to eventually grow weary of voting and of democracy itself). Our constitutional system protected us from Father Coughlin and Joseph McCarthy, and it will protect us from Donald Trump. But let’s not pretend we can’t see exactly what’s going on and what it means.

[See “Part II” here.]