The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows”: Why does this work?

Wednesday, August 1st, 2012 • Writing

So “The Beatles” (a business entity consisting of Sir Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono, Olivia Harrison, George Martin, George Martin’s son Giles Martin* and a raft of attorneys and corporate infrastructure) have released a “new” digital-only album called “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which is a collection of fourteen tracks from the Beatles’ back catalog. All the songs are from what I think of as the “astronomical main sequence” except for the “Naked” version of “I’ve Got a Feeling” (a near-identical adjacent take) and the “Anthology” version of “The End” (which, unlike the “Abbey Road” version, lets you hear the beginning of the song, wherein the Beatles take 16 bars to build up that indelibly ferocious momentum that George Martin’s perfect splice from “Golden Slumbers” air-drops us into as deftly as Daniel Craig landing inside an exploding train and adjusting his cufflink).

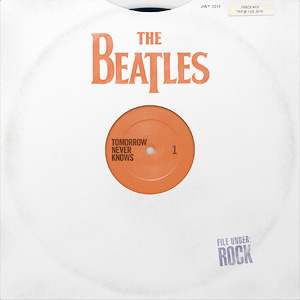

What is this “album”? Can we even call it an “album,” or is it ontologically indistinguishable from a “tracklist”? I, myself, put “Tomorrow Never Knows” together in iTunes in about ten minutes, for free. But, when I listened to it, it nonetheless felt like listening to a record, as intended: the exquisite album art (the only expenditure in the entire release) seems designed to force this interpretation with its aggressively retro “battered vinyl sleeve” design, complete with ersatz dirt and false rubber stamps (“FILE UNDER: ROCK”) and handwritten labels. (It’s even faker than the “handwriting” on The Who’s fake-bootleg “Live at Leeds”: this release not only won’t be pressed onto vinyl but won’t even exist as a compact disc or in any physical form at all; it’s an intellectual abstraction coupled with a pretty picture.) The new “release” is (as has been pointed out elsewhere) formally similar to “Love Songs,” the “red album,” the “blue album” and several other Capitol/EMI compilation records (actual vinyl records) released in the 1970s and 1980s, back when the Beatles were more recent than Nirvana is now. But in those days, before Walkmans, before iTunes, before portable Mp3 players, those discs were necessary; they were the best way for my generation to discover the band. Why, in this era of bittorrent and YouTube fair-use-exploiting videos and traded hard drives with hundreds of overcompressed songs, does this work? Why is this “album” charting in England? Why are we rewarding the remains of “Apple Corps” with more money?

Because it sounds so good. Some obsolete element in my lizard brain sees the circular window in the fictional “sleeve” revealing the fictional “label” with the little hole and conjures up an imaginary turntable and an imaginary tonearm and even a point where the record must be turned over (right before “Back In The U.S.S.R.”) and I’m sold. It’s better than the countless Beatles tracklists I’ve made myself simply because it’s official: because it was assembled by George Martin (or his son, or somebody endorsed by him) rather than a mid-Seventies Capitol Records AOR-executive; because it’s a spectacular set, a mix tape made by the band itself; because the songs, after all this time and all those thousands of listens and the decades it took me to memorize every note, just need to be tweaked into a clever new order to become as fresh and vital as whatever Thom Yorke and Nigel Godrich have on their laptops. It’s not even chemistry; it’s alchemy—the elements do not re-bond into new compounds; they remain exactly as they were, but the ancient magic, the rhythms Aristotle believed would rattle the foundations of the Polis, are re-generated into gold one more time. It’s no accident that the title track is the notorious nonlinear experiment (called “Phase 1” when it inaugurated the “Revolver” sessions) for which AMC paid a quarter of a million dollars in order to allow Don Draper’s moddish wife to persuade him to listen to on Mad Men, and then impatiently turn off, only to have the track return like the molten Terminator—or the finger-blistering end of “Helter Skelter” (also included here) which fades back in for its zombie-like stagger to the finish line. Don Draper can’t stop the Beatles in AMC’s artifically-reconstituted 2012 simulacrum of 1966 and neither can anyone else.

ADDENDUM: Rehabilitating not one but two of the “throwaway” contractual-obligation tracks from “Yellow Submarine” (Harrison’s “Only a Northern Song” uses “contractual obligation” as its subject matter) is cheeky, unabashed brilliance. Even Tim Riley grudgingly laments the Beatles’ late-1967 creative slump (the calm before the “White Album” storm), but “Hey Bulldog” and “It’s All Too Much” are so flattered by this fresh presentation that I have trouble believing they’re still the same tracks I’m familiar with.

*Giles Martin is the man responsible for digitizing the entire canon of 4-track and 8-track recordings (not the cleaned-and-reconverted stereo and mono mixdowns released two years ago but the original multitrack studio masters), producing The Beatles Love Cirque Du Soleil mashup collection as a side-effect of that archival procedure—essentially, disassembling and recombining the songs’ elements into new crystal-pattern alignments; a “Goldberg Variations” alternative to the main compositional library.