Psycho

Wednesday, October 10th, 2007 • Horrorthon Posts / Horrorthon Reviews

You know what I think? I think that we’re all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out. We scratch and claw, but only at the air, only at each other, and, for all of it, we never budge an inch.

1960 (*****)

My Horrorthon “Masterpiece Series” continues with Psycho (1960), the modestly-budgeted, small-scaled black-and-white chiller that is often called “the greatest horror film ever made.” (I won’t get into whether it is or not, since that kind of statistical, Almanac-style critique is especially tedious in the popular arts, where the best examples warp and re-define the criteria in a way that makes choosing a single “best” example nearly impossible.) While it may or may not be “the best,” Psycho is without question a movie that has influenced the genre so overwhelmingly that nearly every horror/thriller film made since owes a debt to it.

Director Alfred Hitchcock is one of several artists whose career peaked almost exactly halfway through, with a series of two or three masterpieces in a row: I’m thinking of the Beatles with Sgt. Pepper (1967) and The Beatles (The “White Album”) (1968) or Stanley Kubrick with Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1973) or Woody Allen with Annie Hall (1977) and Manhattan (1979). When this happens, the individual works in question have almost a diamond-like precision, as if the artist has finally come to understand precisely what he or she is really doing, in the grandest sense, and is therefore able to focus on the task of making a perfect example of their art. Psycho — which followed Vertigo (1958) and North by Norhwest (1959) — is no exception.

Like John Woo and Paul Verhoven, Hitchcock is one in a long series of foreign directors who were lured to America by producers curious to discover how their intriguing or innovative techniques would translate into a more high-budgeted, glamorous environment with big stars. David O. Selznick famously gave Hitchcock a chance at his first American production with Rebecca (1940), which was nominated for 11 Oscars and won 2 (including Best Picture). Thus began a Spielberg-like winning streak of financial and critical successes that made Hitchcock both the most popular and one of the most critically praised directors of his time. However, twenty years after Rebecca, following several complex, high-budget Technicolor productions in a row, Hitchcock famously decided to strip away nearly all of the cumbersome filmmaking apparatus he had developed and return to the simple, direct black-and-white techniques he began with in England, before he migrated from the British filmmaking culture to Hollywood.

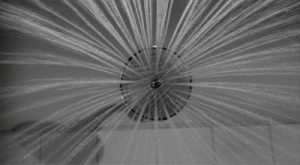

Putting together a small, efficient production crew culled mostly from his anthology TV series (Alfred Hitchcock Presents), Hitchcock bought a mediocre Robert Bloch novel called Psycho and hired established screenwriter Joseph Stefano to simplify and re-shape its story into a lean, clear narrative. Every other element of his filmmaking process was correspondingly cleaned, simplified, and pared down, including the contributions of his favorite long-time collaborators: Just like Spielberg always uses John Williams music and ILM (even on Schindler’s List), Hitchcock always used composer Bernard Herrmann (whose first movie was Citizen Kane and last movie was Taxi Driver — beat that!) and title designer/visual consultant Saul Bass, but even those two Hitchcock fixtures got into the minimalist spirit of the project: Herrman created a score performed entirely on strings, and Bass built the movie’s title sequence around simplified patterns of sweeping white and black lines that shimmer and oscillate unnervingly, foreshadowing the dark madness at the core of the story.

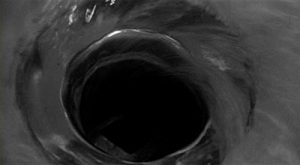

Psycho is deceptively simple, like the best work of Matisse or Corbusier; it has a handful of characters and settings and can be summarized in two or three sentences. But the movie has tremendous depth. In fact, it may be one of the deepest, most complex works of art ever created; hundreds of critical essays over the decades (including Donald Spoto’s book-length scene-by-scene analysis) have examined and explored the piece through the lenses of Freudian symbolism, surrealism, and pictorial and narrative theory. This is the only movie I know of to not just be remade, but remade shot-for-shot (by Gus Van Sant in 1998), which is a testament to the precision of the filmmaking; the camera moves and the cuts and sound effects are so completely integrated into the story that you arguably cannot change a stroke without it not being Psycho any more. I promise not to delve too deeply into the various post-structuralist readings and abstruse theories (even though I love that kind of thing), but suffice it to say that the reservoirs of meaning in the film seem nearly as bottomless as the central blackness of the story is impenetrable; despite its modest story, Psycho appears to provide a fleeting glimpse into the darkest and vastest abysses of the universe.

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is a clerk at a Phoenix, AZ real estate office with a hunky, divorced boyfriend named Sam (John Gavin) whom she routinely meets for trysts on her lunch breaks. Sam, a hardware-store owner in nearby Fairvale, CA, cannot marry her due to his own crippling financial problems (alimony and family debt); the couple is clearly suffering from the impropriety of their arrangement and the strain of his constant payments to his ex-wife, creditors and other “people who aren’t there.” Sam is not the only one suffering: “They also pay who meet in hotel rooms,” Marion points out (and, later, she will discover the real truth of that statement). (“People who aren’t there” is a meaningful phrase too, as the viewer will eventually learn.) Marion is a realistic case study; an ordinary law-abiding citizen introduced at the exact moment that she impulsively and unexpectedly slips over the edge into criminal behavior. A large sum of cash is entrusted to her for deposit in the company’s bank account, and the first half-hour of the movie (shot in blindingly bright, cloudless broad daylight) follows her step by step as she hesitatingly goes through the motions of stealing the money and leaving town with it, enacting a not-very-well-thought-out plan to bring the cash to Sam and free him from his wage-slave financial prison so that they can run away together.

I don’t know what to say about this half-hour opening sequence without getting into superlatives. Not only does Hitchcock gently ratchet up the tension (As Marion drives farther away from town and deeper into trouble, she hears the imaginary voices of Sam and her co-workers as they reluctantly conclude that she has stolen the money) and broaden and darken the visual landscape during her relentless drive North by Northwest, but the road she is traveling and the people she meets (a suspicious California Highway Patrolman; a fast-talking used-car salesman who lets her trade vehicles but is visibly mistrustful) are elements in a foreboding, primal American landscape that make it impossible not to universalize and emotionally connect with Marion’s story, on several levels at once: she is a white-collar fugitive on the run, driving away from dangers and problems that she obviously (and knowingly) cannot escape, but, beyond that, Marion is on the wrong road and Hitchcock is making sure you understand that this road leads to a place she really should not go, and you find yourself increasingly wishing that she change her mind and turn back. But she never turns back, and day turns into night; clear weather turns into violent rain that somehow causes her to make a wrong turn (although it’s never clear when the wrong turn occurs) and soon she is off the main highway, lost and tired and looking for a place to spend the night.

The Bates Motel, where all 12 rooms are vacancies — since “they moved the highway away,” as young proprietor Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) explains — looms out of the rain like a deadly, mythic terminus. Marion finds the place deserted, but honking her horn summons Bates down from the gothic house that stands behind the cabins, where a silhouetted figure paces behind a solitary lit window. (Every image from this part of the movie has become so indelible and iconic that, to a modern viewer, Marion seems to have walked into a famous painting.) Bates invites Marion to join him for a late supper (which he brings down from the house), but his hospitality causes a bitter argument with his mother (the figure in the window) which Marion overhears.

After she hides the stolen money, Marion and Norman sit down in the motel parlor, which is decorated with stuffed birds (this is Bates’ hobby), and have one of the most exhaustively analyzed conversations in cinema (partially quoted above) in which Bates talks movingly about being trapped in the motel business due to his elderly and infirm mother; Marion sympathizes with his cruel treatment, while apologizing for intruding, and unexpectedly begins talking about the “private trap” she’s stepped into. Bates is offended at her suggestion that his mother be institutionalized, but ultimately agrees that his situation is unacceptable. The two clearly like each other, and communicate in a compelling and meaningful way; the conversation apparently convinces Marion to face up to what she’s done, reverse her plans and drive all the way back to Phoenix the next morning, after a shower and a good night’s sleep. (After she’s returned to her room, Norman reveals his boyish prurient interest in her by uncovering a spy-hole through which he can watch her undress.) Then, forty-six minutes into the movie, Marion gets into the shower and it’s the last thing she ever does.

The murder scene (which comes out of nowhere) is justifiably famous; probably the most famous murder in film history. These days, such shocking twists are commonplace, but in 1960, nobody in the audience could possibly have expected the main character to be violently murdered less than halfway through the movie. There are scores of essays and analyses of the “shower sequence” that do a far better job than I ever could explaining the music, the cutting and the eye/drain/water/blood/curtain symbolism; suffice it to say that the metaphysics does not in any way impede the pure shock value and terror of the scene; when it’s over, and Norman is now, suddenly, the main character (trying desperately to cover up his mother’s crime) we have gone through the looking glass into an inverted nightmare world. The remaining hour of the movie — as Sam returns to the story, investigating Marion’s disappearance along with her sister (Vera Miles) and a private detective (Martin Balsam) hired by the Phoenix realtor — never quite matches the intense brilliance of the portion I’ve described in such detail, but there are several more twists to come, including a final shocker that’s about as good as any twist ending the genre has ever seen.

Is Psycho, like Roy Hobbs, “the best there ever was”? Maybe and maybe not, as I said up top (and I reiterate my distaste with the question). It may not even be Hitchcock’s primary masterpiece; that’s probably Vertigo (which isn’t a horror film at all; more of a traditional mystery/suspense thriller). But Psycho singlehandedly invents, exemplifies and transcends the slasher genre, and it would be difficult to find a more flawless example of the form. The Bates Motel anchors down a corner of the nightmare landscape deep in all of our subconscious minds; it’s the place you go when the storm drives you off the main road into chaos and madness; although it may look like a simple pair of buildings in the California desert, it’s really a gateway into ultimate darkness, and if you go there, you’ll never come back.